Detecting And Decoding Ezpass Phishing Activity In The Wild Part 1

Disclaimer: This article is for research and educational purposes. Do not visit phishing websites without proper precautions.

Did you ever get those text messages saying you have a package waiting for USPS? Or do you have a package waiting from Amazon? What was once isolated to emails has expanded into text messaging: smishing attacks. For simplicity, we will stick with the term phishing. A phishing attack aims to present itself as a legitimate source to its victim, so the victim reveals login credentials, credit card numbers, or worse. Overall, the advice is not to engage with suspected phishing messages and always report them. But…what about for research purposes?

Phishing scams come and go. I’ve found that articles can go into serious technical details about the big bois; especially with malware analysis. But I didn’t see much on covering the E-ZPass scam. Many people know what you are talking about, but not much past it. This boils down to two things: the threat actors are disjointed groups of scammers with no single figure to point the finger at. The other reason is that the infrastructure is ephemeral and hard to pin down. You blink, and that phishing site you could investigate is gone.

This is something I ran into over the course of my research, but there is more to it.

Unfortunately, I don’t get to the bottom of it in this article, so I decided to make this a series. I aim to walk through interesting things I found from a single link and the tools I used. Hopefully, this can be useful for anyone interested in hunting for Indicators of Compromise (IOC) or someone just curious.

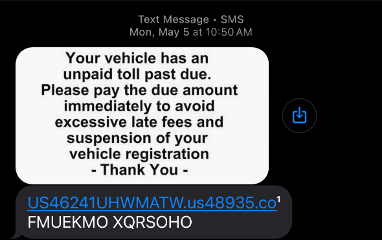

The Text Message

This journey started while I was at work. I had been reading a lot about adversarial infrastructure lately, and when I got this message, it would be the perfect opportunity to test out what I had been learning.

The link to the site is in blue. I waited until I got home and used Any Run to visit that site. I like using Any Run because their community sandbox is free, but there are alternatives. Unfortunately, I received a 404 Not Found status.

Fortunately, we have more tools in our toolbox.

The Pivot(s)

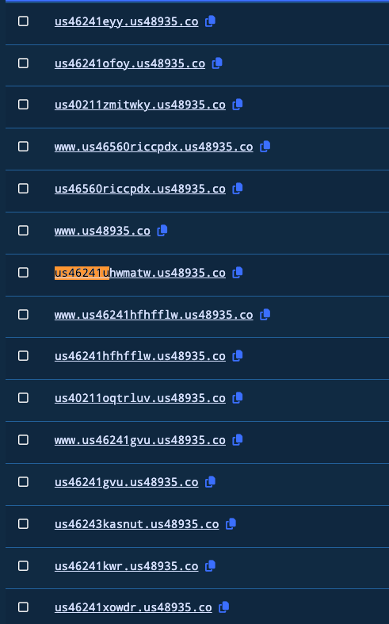

I didn’t take a screenshot when I visited that URL, but I noticed it had changed. Fortunately, the internet never forgets. Passive DNS is great for moments like these because it keeps historical records of previous scans. I have enjoyed using Validin for my historical research, but there are other resources. I searched for my initial URL and found a bunch of additional subdomains in a similar nonsense format.

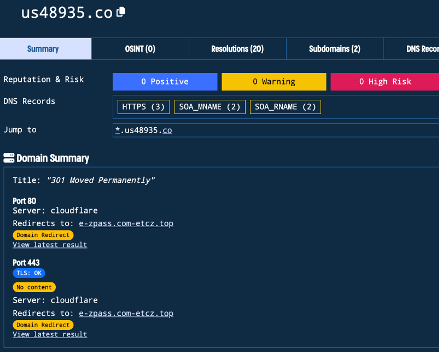

So I pivot to primary domain us48935[.]co and find the EZpass URL I was looking for: e-zpass.com-etcz[.]top.

This is my first pivot.

NOTE: I do want to caveat that since researching this site no longer redirects to that EZPass URL. Remember, their infrastructure constantly changes to hide their tracks.

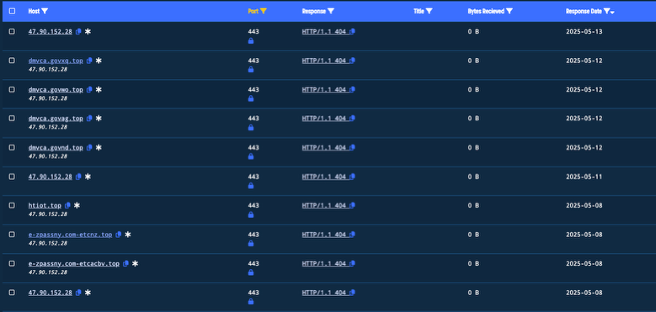

I go to the Resolutions tab and get an IP address of 47.90.152[.]28. I found something very interesting when I pivoted: 164 resolutions!

Now I see a pattern in how they come up with their domains. E-ZPass is consistently their subdomain. Then, they are using com-xxx[.]top as their primary domain. As we will find, these are all dead ends! There are 404 status codes for everything.

We will cover on what may be happening later. But I wanted to cover a couple of pivot points to look at before developing theories…

Certificates and HTTP Headers

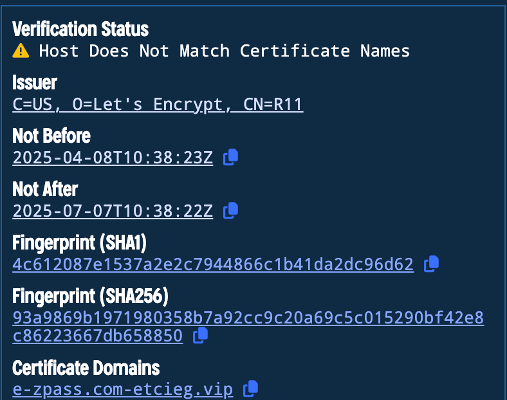

Without getting into the weeds, most websites have a certificate for their connection. This is used to encrypt connections and validate the website you are visiting. However, this can be abused if left in the wrong hands. Certificates have thumbprints, and thumbprints can be pivots. But as we go through the certificate thumbprints, we find a lot of one-off certificates (take my word for it).

So, I decided to pivot off the HTTP headers. Think of an HTTP Banner as an address for services running on a server. It has the protocol, server version, and other miscellaneous items that make it unique to that service. In our case:

1

2

3

4

HTTP/1.1 404

Server: nginx/1.27.4

Content-Length: 0

Connection: keep-alive

I omitted a piece of the header to continue tracking the threat actor. In part two, I will explain why in more detail. HTTP Headers are useful for threat hunters because if a threat actor is reusing their configurations and it is unique enough, they can use it to find additional infrastructure. Shodan is an excellent tool for researching HTTP headers. This header will provide LOT of results, and the scent has been reinvigorated…or overwhelmed with over one thousand results on Validin.

AND we have uncovered a new target state DMVs as well as other targets. Such as dmv-ca.gov-chen[.]win. But for this article, we will stay focused on E-ZPass. I filtered my search down to “pass.com-“ to see what variations I get. I reduced it to 283 results. Here is a sample:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

ezpass[.]com-ezib[.]vip

e-zpass[.]com-etciotg[.]cc

e-zpass[.]com-ioteo[.]cc

e-zpass[.]com-iotet[.]cc

e-zpass[.]com-vioa[.]cc

e-zpass[.]com-tolliunb[.]icu

e-zpass[.]com-tolliupz[.]icu

e-zpass[.]com-etcioj[.]icu

e-zpass[.]com-etciott[.]cc

There’s a lot of variation, but we start seeing patterns. The threat actor is using a general pool of tolling services as the subdomain and variations of “com — .” A security analyst would make an alert rule for this pattern to prevent an intrusion from this threat actor. They would do this by using Regular Expressions (Regex) to be more efficient than uploading all these results individually. Here is what this one would look like:

1

.*\.com-[a-z]{4,10}\.(cc|icu|top)

All you need to know about this is that it considers 4 to 10 characters after com- from the alphabet a-z. There are other variations I found, but let’s stay focused on this pattern.

As I mentioned, we will find certificate reuse. What was probably intended as a one-off certificate ends up being bound to other domains. As we find here for com-etcvfy[.]VIP:

After pivoting to that certificate, we see another pattern:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

com-etcvfy[.]vip

com-etcvfq[.]vip

com-etcvfo[.]vip

com-etcvfr[.]vip

com-etcvft[.]vip

com-etcvfu[.]vip

com-etcvfp[.]vip

com-etcvfi[.]vip

com-etcvfw[.]vip

com-etcvfe[.]vip

The naming convention isn’t as random as initially thought. There is an increment of change on the last character of the primary domain.

Part One Conclusion

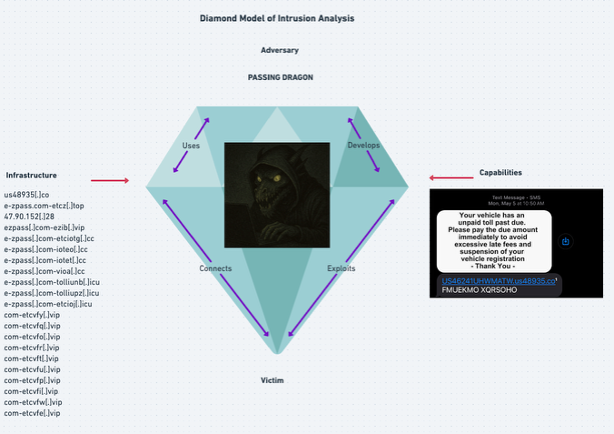

The threat actor is targeting US citizens with state government and private services. This is an ongoing investigation, so I don’t want to reveal everything I found. This threat actor is still conducting operations. I omitted some artifacts to learn more about the threat actor. I will discuss these techniques in part two as I gather more intelligence. I am open to collaboration and share all my IOCs privately.

I will use the Diamond Model to illustrate what I have discovered. I will be calling this threat actor Passing Dragon.